To go to the DockATot website is to be transported into a world of idyllic childhood. You’ll see photos of its latest collection showing playrooms with flowing drapes, tasseled blankets, and ornate floral arrangements. At the center are cherubic infants nestled in plush, pillowy products resembling bassinets. “Love, luxury and timelessness are at the heart of this exclusive new collection for style-conscious parents,” a description says.

The message: Chic nursery designs can be yours, too—for about $200 to $300.

What you wouldn’t know is that the DockATot and other “in-bed sleepers,” as the products have come to be known, have been linked to at least 13 infant fatalities, according to an ongoing Consumer Reports investigation of government data and lawsuits.

The products were originally marketed to parents who wanted the closeness of sharing a bed with their babies but worried about rolling onto them. And while bassinets, cribs, and many other infant sleep products have to, by law, adhere to established safety standards and be tested to prove they meet them, in-bed sleepers do not.

In fact, there has been nothing to stop the products—which have significant safety shortcomings—from making their way onto store shelves and into people’s homes.

DockATot did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Gaps in the System

This gap in the product safety system is not unique to in-bed sleepers, or even to baby products. Products often are not required to comply with safety specifications and, for many, “there is no premarket safety testing required,” says Rachel Weintraub, legislative director and general counsel for the Consumer Federation of America, an advocacy group.

Of the approximately 15,000 categories of products overseen by the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the government agency with jurisdiction over many consumer products, only about 70 are governed by what is called a mandatory standard, according to an estimate by Bob Adler, acting chairman of the CPSC.

For those 70 product categories, federal rules mandate compliance with specific safety requirements. Manufacturers must test them, usually through third-party labs. Products that fail these tests must be recalled if they’re already for sale. If the manufacturer has violated the law—for instance, by failing to immediately report a noncompliant product to the CPSC—it can face penalties, such as fines and even criminal prosecution.

Products with mandatory standards include bunk beds, children’s toys, automatic garage door openers, walk-behind lawn mowers, high chairs, bicycle helmets, and portable gasoline containers. There are also federal requirements for materials—including metals, plastics, and textiles—related to toxic substances, such as lead.

But most products are governed by voluntary, not mandatory, standards created by independent organizations. These groups—among them ASTM International and Underwriters Laboratories—bring together manufacturers, academics, regulators, consumers, and others to set rules for the products. (CR is a member of ASTM.)

Product Testing

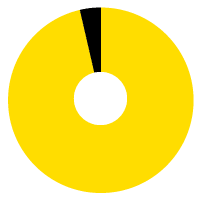

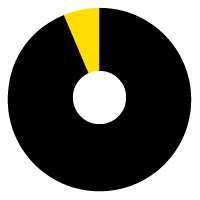

96% of Americans believe products they buy for their home must adhere to a required safety standard.11 Based on a July 2020 CR nationally representative survey of 2,031 American adults. Respondents were asked to focus on products that cost $75 or more. Percentage includes “agree” and “strongly agree” responses.REALITY

<1% of product categories overseen by the CPSC must comply with a mandatory safety standard. 22 Estimate from acting CPSC chairman Bob Adler.

But because these standards are voluntary, some manufacturers don’t comply with the rules, leaving a hole in the safety net, Weintraub says.

In addition to products with mandatory or voluntary standards, a smaller set of products—which includes in-bed sleepers—is not covered by any specific standard. While they must adhere to certain broad, general rules—such as not containing high amounts of lead—they may be new and different enough from other products that they don’t need to conform to an existing standard, whether mandatory or voluntary.

In other words, if someone invents something substantially different from products in existing categories, they can put it on the market even if it has not been safety-tested. Manufacturers don’t have to first get approval from the CPSC or any other governing body.

That is how in-bed sleepers made it to market. It’s also how the Fisher-Price Rock ’n Play Sleeper and other inclined sleepers, which are now linked to 94 deaths, got to store shelves and stayed there for a decade before being recalled.

“This contradicts what many consumers think—that if a product is available for sale, it has been tested and approved,” Weintraub says.

Product Recalls

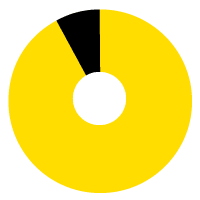

92% of Americans say manufacturers should do all they can to get potentially dangerous recalled products out of homes.11 Based on a July 2020 CR nationally representative survey of 2,031 American adults. Respondents were asked to focus on products that cost $75 or more. Percentage includes “agree” and “strongly agree” responses.

6% of recalled products, on average, are returned or refunded. 22 CPSC, July 2017. Reflects portion of consumers whom the CPSC knows took part in a recall, including those who asked for a repair.

Indeed, 96 percent of Americans believe products they buy for their home adhere to a required safety standard, according to a 2020 nationally representative CR survey of 2,031 adults, which asked people to focus on products that cost $75 or more. And most people—97 percent—said they expect that manufacturers have tested their products for safety before selling them.

“It would be nice to know that every single manufacturer, whether there’s a voluntary product standard or not . . . [has] done some kind of reasonable testing,” Adler says. But, he adds, that is not always the case—and there is no easy way for consumers to know one way or the other.

What’s a ‘Standard,’ Anyway?

Nancy Cowles, executive director of Kids In Danger (KID), a consumer safety group, says there’s another potential problem: Just because a voluntary standard exists doesn’t mean it’s strong enough. For many products, “the existing standard is less than rigorous,” she says, adding that the standard-setting process tends to favor industry over consumers.

One glaring example: the voluntary standard for dressers, first set by ASTM in 2000 and updated incrementally over the years. It currently says dressers 27 inches high or taller should remain stable when a 50-pound weight is hung on an open drawer. But almost from the start, safety advocates have said the standard is not tough enough.

Indeed, despite updates to the standard over the years, 218 people died in tip-over incidents involving a dresser, chest, or bureau between 2000 and 2019. And each year, 19,900 people, on average, are treated in hospital emergency rooms for injuries related to furniture tip-overs.

Also, not all manufacturers comply with the standard; after all, it is voluntary. For years, many of Ikea’s dressers did not meet the standard, and some have been linked to the deaths of several children, leading to the recall in 2016 and 2017 of 17.3 million products.

Safety advocates, including those at CR, say the voluntary dresser standard is still not strong enough. They support legislation called the Stop Tip-overs of Unstable, Risky Dressers on Youth (STURDY) Act. It would require the CPSC to create a mandatory rule tougher than the voluntary one. The bill, which passed the U.S. House of Representatives in the last session of Congress but did not make it to the Senate floor, has been reintroduced this year in both chambers and has bipartisan support.

The CPSC’s Adler says he could not have predicted “how lethal” dresser tip-overs could be. “It’s only after you’ve done some appropriate safety testing that you realize there could be a problem,” he says.

Another product whose dangers emerged after entering the marketplace: cords for window blinds and shades. They did not have a voluntary safety standard until 1996. Yet between 1990 and 2015 they were linked to almost 17,000 strangulations, lacerations, and other injuries, and 271 deaths among children younger than 6, according to research in the journal Pediatrics.

Too often, Adler says, companies ask themselves whether their products simply “comply with appropriate standards, and what we need them to do is look beyond the standards to whether there’s a potential for harm.”

Jonathan Judge, a partner at the Chicago law firm Schiff Hardin and a CPSC regulation expert who counsels manufacturers, disputes the idea that standards are often weak and that companies don’t do enough to vet their products. “The vast majority of companies really do think about this,” he says. “They’re not interested in having a bunch of returns or a bunch of bad publicity.” He also says that when no standard exists for a new product, companies often adapt existing ones.

But that approach might not sufficiently protect consumers from risks that emerge only after a product enters the market. “Safety hazards don’t always announce themselves,” Adler says.

4 Products That Lack Safety Standards

We checked with five major standard-setting and accrediting organizations in the U.S. to see whether these consumer goods have an applicable safety standard. As of April 2021, they did not.

HOVERBOARDS

Until 2016, there was no standard covering hoverboards’ electrical systems, and some caught fire and were recalled. They’re still not subject to standards governing acceleration, braking, or durability, problems consumers have complained about, though such standards are being developed.

SNORKELS

At least one model was recalled because a piece broke off and was inhaled by a user. Recreational snorkels are not subject to specific standards, as some diving gear is.

E-SCOOTERS

Some adult and ride-sharing e-scooters have broken or caught fire, leading to injuries and recalls. While children’s e-scooters have some safety standards, a performance standard for adult versions is only now being created.

INFANT SLEEP HAMMOCKS

Some of these products have been linked to injuries and deaths and have been recalled. These products don’t conform to safety standards or follow safe-sleep advice that babies sleep on their back on a firm, flat surface.

To Market, Without Testing

Products marketed for babies and children are of particular concern because the stakes are so high.

In the case of in-bed sleepers, two products were introduced in the early 2000s by two entrepreneurial women working separately on the same goal: to create a product that babies could sleep in while lying next to their parent in bed. But the products’ potential hazards were apparent almost as soon as they came to market.

Cribs and bassinets must adhere to mandatory standards that require high walls, a flat mattress, a stand, and no padding. That helps protect against suffocation and is consistent with advice from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) that babies sleep alone, on their backs, on a firm, flat surface free of soft bedding. By contrast, in-bed sleepers tend to have padding and lower, softer sidewalls. And because they have been marketed for use on an adult mattress, they do not necessarily provide a firm, flat sleep surface.

Lisa Furuland Kotsianis had no known experience in product development or child safety before she created the DockATot. Instead, she relied on her experience as a mother and her “background in art, design, and photography” to develop “category-disrupting must-haves,” according to the company website.

Similarly, Farah Morton invented the Baby Delight Snuggle Nest in-bed sleeper because she “realized the bassinet she was using prevented the closeness she desired with her newborn daughter,” says a Baby Delight spokesperson, who also says Morton no longer owns the company. According to what appears to be Morton’s LinkedIn page, she developed the product “in order to provide more protection for co-sleeping newborns, opening a category that previously did not exist.”

The spokesperson, when asked whether premarket testing was done to ensure that the product was safe for infant sleep, says Morton “engaged a seasoned safety consultant at the time of the first manufacturing.”

THE PROBLEMS WITH IN-BED SLEEPERS

- It Has No Stand That makes it unstable, especially when placed on an adult mattress, which can be uneven, increasing the risk of an infant rolling out or into a soft wall.

- The Bottom Is Too Soft The base should be firm, to reduce the chance of suffocation if an infant rolls over.

- The Walls Are Too Low They should be high enough so that babies can’t roll out.

- The Walls Are Too Padded Soft walls increase the risk of suffocation if an infant rolls to the side and presses against the padding.

Though DockATot recently stopped explicitly promoting its product for bed-sharing, as of this April its marketing still showed images of babies sleeping in the product and pictures suggestive of bed-sharing. No details about premarket testing for sleep safety are provided on its website.

Consumers have responded to the products enthusiastically. The Snuggle Nest has become a best seller for Baby Delight, according to a company spokesperson. And the DockATot caught on with celebrity influencers such as Molly Sims, Kourtney Kardashian, and Hilary Duff, who raved about it on social media and in other outlets.

The product’s popularity is concerning, says Ben Hoffman, MD, chairperson of the AAP Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. “If you go back to what we know is the safest way for an infant to sleep, in-bed sleepers missed the mark on virtually all accounts,” he says. It’s also unknown, he says, whether in-bed sleepers prevent adults from rolling over and smothering infants. “Basically, the products don’t do anything we would ever expect in a safe sleep space for a baby.”

Manufacturers Are Writing Their Own Rules

Despite Hoffman’s concerns, the makers of in-bed sleepers are now creating their own voluntary standard through ASTM. Whether the products should conform to the bassinet standard, or be sold as loungers instead of as sleep products, is among the concerns that regulators, safety advocates, and industry representatives are debating.

The discussions are taking place against the backdrop of the CPSC’s proposal of a mandatory rule for infant sleep products, which was developed after the high-profile recalls of infant inclined sleepers, including the Fisher-Price Rock ’n Play Sleeper. The agency’s new rule would effectively ban infant sleep products that don’t conform to existing mandatory standards.

After the rule was proposed, DockATot changed its messaging. As of April 2021, its website stated: “Until there is further development on a mandatory standard for all products offered for bedsharing, we will no longer promote our docks for use in bedsharing.”

As of April 2021, Baby Delight continued to market the Snuggle Nest for bed-sharing. Of the three fatalities that have been linked to the Snuggle Nest, a spokesperson says that two occurred before the company acquired the product and that none were directly caused by the sleeper. The spokesperson also says the product fills a consumer need: “We know that moms co-sleep,” and the product’s goal “is to make that experience less risky when possible.”

That argument is based on a false premise, says Nancy Cowles of KID. “There is no data we know of showing that in-bed sleepers make bed-sharing safer,” she says. The AAP’s Ben Hoffman says the opposite may even be true. “We know that the likelihood of infant sleep-related deaths goes up when you start deviating from best safe-sleep practices,” he says. “When you’ve got products that facilitate dangerous sleep behaviors, that increases risk.”

Further, to safety advocates, the idea of working backward to create a standard for a product that’s already being sold but hasn’t been safety-tested brings back bad memories of the Rock ’n Play Sleeper. “The dangers of inclined sleepers were hidden from the public for nearly a decade, and infants died,” says Oriene Shin, CR policy counsel for product safety. “Manufacturers sold dangerous products by the millions, and only tried after the fact to create standards to validate their safety. Why would we want to go down that path again?”

When the Rock ’n Play Sleeper was introduced in 2009, no voluntary or mandatory standard existed for inclined sleepers. But in 2010, when the CPSC began updating standards for bassinets, cribs, and play yards to make them mandatory, it became clear that the Rock ’n Play Sleeper—with its incline and padding—would not comply.

But instead of changing its design, Fisher-Price asked for, and was granted, an exemption. That freed manufacturers to create their own voluntary standard through ASTM—and to continue selling inclined sleepers. It was only in 2019, after CR exposed dozens of deaths connected to the sleepers, that Fisher-Price and others recalled them. Such recalls now total almost 6 million.

It is a cautionary tale, says Regina Calcaterra, a lawyer representing several families whose children died in the Rock ’n Play Sleeper. “Before the CPSC again delegates potentially lifesaving standards for infant sleep products to ASTM,” and “then to manufacturers who financially benefit, CPSC commissioners should hear from the parents who are grieving,” she says.

CR’s Shin adds: “Manufacturers shouldn’t be in charge of their own safety rules.” Instead, she says, “there should be a much stronger and better-funded CPSC that can get ahead of emerging hazards and hold companies accountable from the start—including by stopping them from carving out exceptions for unproven products, like in-bed sleepers.”

The CPSC’s Adler says the agency is doing as much as it can with the little funding it gets, adding that he hopes Congress will increase CPSC funds. That’s necessary to protect consumers, he said in a recent address. “As long as entrepreneurs dream up new products and chemists develop new concoctions, new safety hazards will always emerge.”

How to Protect Yourself

Though it’s not always easy, here are some steps you can take to find out whether a product has been safety-tested or vetted.

Read the labels. A product’s packaging, manual, or tag may reference a standard-setting or standard-certifying organization, such as ASTM or UL. That reference might note which specific standard applies to your product, such as “ASTM F2057-19” or “UL 749.” For more on labels, see the chart below.

Call the manufacturer. If there is no label or standard shown on the product, call the company and ask what safety standards the product meets and whether a third-party lab has verified this.

Check SaferProducts.gov. On this CPSC website, you can learn whether a product has been recalled. And if you have an unsafe product or one that has caused harm, you can report it on the site.

To read the full article, click here.