Fixed-Rate vs. Adjustable-Rate Mortgages: An Overview

Fixed-rate mortgages and adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) are the two primary mortgage types. While the marketplace offers numerous varieties within these two categories, the first step when shopping for a mortgage is determining which of the two main loan types best suits your needs.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- A fixed-rate mortgage charges a set rate of interest that does not change throughout the life of the loan.

- The initial interest rate on an adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) is set below the market rate on a comparable fixed-rate loan, and then the rate rises (or possibly lowers) as time goes on.

- ARMs are typically more complicated than fixed-rate mortgages.

Fixed-Rate Mortgages

A fixed-rate mortgage charges a set rate of interest that remains unchanged throughout the life of the loan. Although the amount of principal and interest paid each month varies from payment to payment, the total payment remains the same, which makes budgeting easy for homeowners.

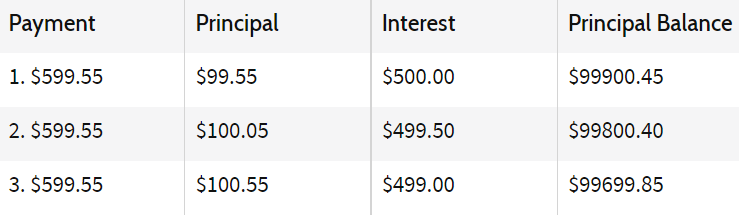

The partial amortization schedule below demonstrates the way in which the amounts put toward principal and interest alter over the life of the mortgage. In this example, the mortgage term is 30 years, the principal is $100,000, and the interest rate is 6%.

As you can see, the payments made during the initial years of a mortgage consist primarily of interest payments.

The main advantage of a fixed-rate loan is that the borrower is protected from sudden and potentially significant increases in monthly mortgage payments if interest rates rise. Fixed-rate mortgages are easy to understand and vary little from lender to lender. The downside to fixed-rate mortgages is that when interest rates are high, qualifying for a loan is more difficult because the payments are less affordable. A mortgage calculator can show you the impact of different rates on your monthly payment.

Although the rate of interest is fixed, the total amount of interest you’ll pay depends on the mortgage term. Traditional lending institutions offer fixed-rate mortgages for a variety of terms, the most common of which are 30, 20, and 15 years.

The 30-year mortgage is the most popular choice because it offers the lowest monthly payment. However, the trade-off for that low payment is a significantly higher overall cost, because the extra decade, or more, in the term is devoted primarily to paying interest. The monthly payments for shorter-term mortgages are higher so that the principal is repaid in a shorter time frame. Also, shorter-term mortgages offer a lower interest rate, which allows for a larger amount of principal repaid with each mortgage payment. Thus, shorter term mortgages cost significantly less overall.

Adjustable-Rate Mortgages

The interest rate for an adjustable-rate mortgage is a variable one. The initial interest rate on an ARM is set below the market rate on a comparable fixed-rate loan, and then the rate rises as time goes on. If the ARM is held long enough, the interest rate will surpass the going rate for fixed-rate loans.

ARMs have a fixed period of time during which the initial interest rate remains constant, after which the interest rate adjusts at a pre-arranged frequency. The fixed-rate period can vary significantly—anywhere from one month to 10 years; shorter adjustment periods generally carry lower initial interest rates. After the initial term, the loan resets, meaning there is a new interest rate based on current market rates. This is then the rate until the next reset, which may be the following year.

ARM Terminology

ARMs are significantly more complicated than fixed-rate loans, so exploring the pros and cons requires an understanding of some basic terminology. Here are some concepts borrowers need to know before selecting an ARM:

- Adjustment Frequency: This refers to the amount of time between interest-rate adjustments (e.g. monthly, yearly, etc.).

- Adjustment Indexes: Interest-rate adjustments are tied to a benchmark. Sometimes this is the interest rate on a type of asset, such as certificates of deposit or Treasury bills. It could also be a specific index, such as the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), the Cost of Funds Index or the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR).

- Margin: When you sign your loan, you agree to pay a rate that is a certain percentage higher than the adjustment index. For example, your adjustable rate may be the rate of the one-year T-bill plus 2%. That extra 2% is called the margin.

- Caps: This refers to the limit on the amount the interest rate can increase each adjustment period. Some ARMs also offer caps on the total monthly payment. These loans, also known as negative amortization loans, keep payments low; however, these payments may cover only a portion of the interest due. Unpaid interest becomes part of the principal. After years of paying the mortgage, your principal owed may be greater than the amount you initially borrowed.

- Ceiling: This is the highest that the adjustable interest rate is permitted to reach during the life of the loan.

The biggest advantage of an ARM is that it is considerably cheaper than a fixed-rate mortgage, at least for the first three, five, or seven years. ARMs are also attractive because their low initial payments often enable the borrower to qualify for a larger loan and, in a falling-interest-rate environment, allow the borrower to enjoy lower interest rates (and lower payments) without the need to refinance the mortgage.

A borrower who chooses an ARM may save several hundred dollars a month for up to seven years, after which their costs are likely to rise. The new rate will be based on market rates, not the initial below-market rate. If you’re very lucky, it may be lower depending on what the market rates are like at the time of the rate reset.

The ARM, however, can pose some significant downsides. With an ARM, your monthly payment may change frequently over the life of the loan. And if you take on a large loan, you could be in trouble when interest rates rise: Some ARMs are structured so that interest rates can nearly double in just a few years.

Indeed, adjustable-rate mortgages went out of favor with many financial planners after the subprime mortgage meltdown of 2008, which ushered in an era of foreclosures and short sales. Borrowers faced sticker shock when their ARMs adjusted, and their payments skyrocketed. Fortunately, since then government regulations and legislation have been instituted to increase the oversight that transformed a housing bubble into a global financial crisis. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has been preventing predatory mortgage practices that hurt the consumer. Lenders are lending to borrowers who are likely to repay their loans.

Important: ARMs are considerably cheaper than fixed-rate mortgages.

Which Loan Is Right for You?

When choosing a mortgage, you need to consider a wide range of personal factors and balance them with the economic realities of an ever-changing marketplace. Individuals’ personal finances often experience periods of advance and decline, interest rates rise and fall, and the strength of the economy waxes and wanes. To put your loan selection into the context of these factors, consider the following questions:

- How large a mortgage payment can you afford today?

- Could you still afford an ARM if interest rates rise?

- How long do you intend to live on the property?

- In what direction are interest rates heading, and do you anticipate that trend to continue?

If you are considering an ARM, you should run the numbers to determine the worst-case scenario. If you can still afford it if the mortgage resets to the maximum cap in the future, an ARM will save you money every month. Ideally, you should use the savings compared to a fixed-rate mortgage to make extra principal payments each month, so that the total loan is smaller when the reset occurs, further lowering costs.

If interest rates are high and expected to fall, an ARM will ensure that you get to take advantage of the drop, as you’re not locked into a particular rate. If interest rates are climbing or a steady, predictable payment is important to you, a fixed-rate mortgage may be the way to go.

Candidates for ARMs

The Short-Term Homeowner

An ARM may be an excellent choice if low payments in the near term are your primary requirement, or if you don’t plan to live in the property long enough for the rates to rise. As mentioned earlier, the fixed-rate period of an ARM varies, typically from one year to seven years, which is why an ARM might not make sense for people who plan to keep their home for more than that. However, if you know you are going to move within a short period, or you don’t plan to hold on to the house for decades to come, then an ARM is going to make a lot of sense.

Let’s say the interest-rate environment means you can take out a five-year ARM with an interest rate of 3.5%. A 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, in comparison, would give you an interest rate of 4.25%. If you plan to move before the five-year ARM resets, you are going to save a lot of money on interest. If, on the other hand, you ultimately decide to stay in the house longer, especially if rates are higher when your loan adjusts, then the mortgage is going to cost more than the fixed-rate loan would have. If, though, you are purchasing a home with an eye toward upgrading to a bigger home once you start a family—or you think you’ll be relocating for work—then an ARM may be right for you.

The Bump-Up-in-Income Earner

For people who have a stable income but don’t expect it to increase dramatically, a fixed-rate mortgage makes more sense. However, if you expect to see an increase in your income, going with an ARM could save you from paying a lot of interest over the long haul.

Let’s say you are looking for your first home and just graduated from medical or law school or earned an MBA. The chances are high that you are going to earn more in the coming years and will be able to afford the increased payments when your loan adjusts to a higher rate. In that case, an ARM will work for you. In another scenario, if you expect to start receiving money from a trust at a certain age, you could get an ARM that resets in the same year.

The Pay-It-Off Type

Taking out an adjustable-rate mortgage is very attractive to mortgage borrowers who have, or will have, the cash to pay off the loan before the new interest rate kicks in. While that doesn’t include the vast majority of Americans, there are situations in which it may be possible to pull it off.

Take a borrower who is buying one house and selling another one at the same time. That person may be forced to purchase the new home while the old one is in contract and, as a result, will take out a one- or two-year ARM. Once the borrower has the proceeds from the sale, they can turn around to pay off the ARM with the proceeds from the home sale.

Another situation in which an ARM would make sense is if you can afford to accelerate the payments each month by enough to pay it off before it resets. Employing this strategy can be risky because life is unpredictable. While you may be able to afford to make accelerated payments now, if you get sick, lose your job, or the boiler goes, that may no longer be an option.

The Bottom Line

Regardless of the loan type you select, choosing carefully will help you avoid costly mistakes. One thing is for sure: Don’t go with the ARM because you think the lower monthly payment is the only way to afford that dream house. You may get a similar rate at the time of reset, but it is a serious gamble. It’s more prudent to search for a house with a smaller price tag instead.

To read the full article, click here.